By XAMXAM

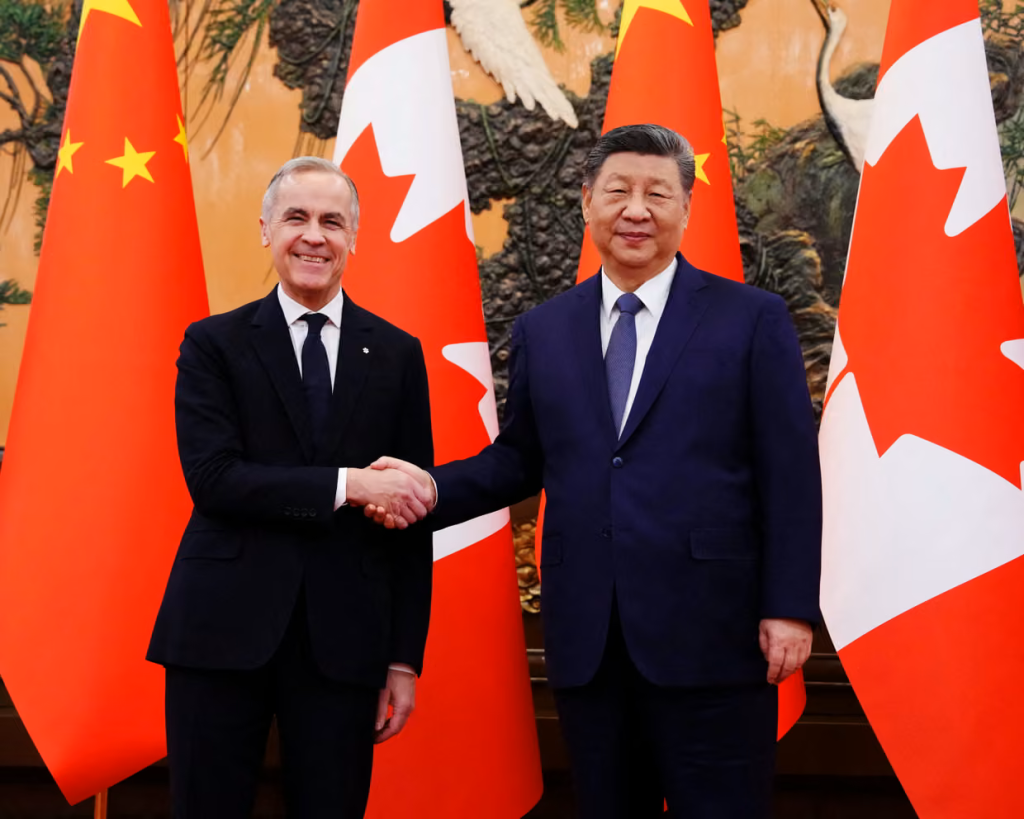

The announcement came from Beijing with little of the drama that usually accompanies a geopolitical rupture. Standing beside Xi Jinping, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney confirmed what many in Washington had hoped would not materialize: a comprehensive reset in trade relations between Canada and China.

Tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles were sharply reduced to 6.1 percent. Canadian approval was granted for the import of tens of thousands of vehicles. Canola tariffs that had reached a punitive 84 percent were cut to 15 percent. And, in a move with symbolic and practical weight, visa-free travel for Canadians to China was restored.

Individually, each measure is significant. Taken together, they represent something more consequential: a deliberate effort by Ottawa to insulate itself from the kind of economic pressure that has increasingly defined its relationship with the United States under Donald Trump.

For years, Trump’s approach to allies relied on a simple assumption—that access to the American market and American infrastructure gave Washington enduring leverage. Tariffs, threats, and public confrontation were tools meant to compel compliance. Canada, deeply integrated into U.S. supply chains, often had limited room to maneuver. That constraint shaped policy choices even when political patience wore thin.

The Beijing agreement suggests that constraint is loosening.

The centerpiece of the deal is electric vehicles, an industry that sits at the intersection of industrial policy, climate commitments, and great-power competition. China is the world’s dominant EV producer, with scale and cost advantages that Western manufacturers have struggled to match. Rather than attempt to wall off that reality, Canada has chosen to engage it—on its own terms.

Under the framework outlined in Beijing, Chinese EVs will not merely enter the Canadian market. Within several years, production is expected to move onto Canadian soil, particularly in Ontario. That distinction matters. Vehicles manufactured in Canada carry different legal and political implications than imports. They mean domestic jobs, local supply chains, and pricing that could place electric cars within reach of middle-income consumers.

They also sit uncomfortably close to the U.S. border.

For Washington, this arrangement undermines a core objective of Trump’s trade strategy: isolating Chinese industrial capacity while pressuring Canada’s auto sector into alignment with American priorities. By hosting production rather than simply importing vehicles, Canada has sidestepped both pressures at once.

Agriculture tells a parallel story. Canola has long been a political fault line, particularly in Western Canada, where farmers absorbed the cost of retaliatory Chinese tariffs linked to broader diplomatic disputes. An 84 percent tariff effectively shut the market. Reducing that figure to 15 percent restores access worth billions of dollars annually and relieves domestic political strain without U.S. mediation.

Just as important is what the deal does not do. It does not position Canada as choosing China over the United States. It does not announce a rupture with Washington. Instead, it narrows the scope of American influence by creating alternatives. That distinction may prove decisive.

Visa-free travel, easily dismissed as a diplomatic courtesy, completes the picture. Business delegations move faster when paperwork disappears. Tourism rebounds quickly. Academic and cultural exchanges regain momentum. These flows build constituencies that favor stability and continuity. Once restored, they are difficult to freeze again without clear cause.

From a strategic perspective, the deal reflects a shift away from leverage politics toward redundancy. Rather than contest every pressure point, Canada has reduced its exposure to them. Supply chains diversified are threats neutralized. Markets reopened elsewhere diminish the power of any single gatekeeper.

For Trump, the lesson is uncomfortable. Leverage erodes when it is overused. Tariffs can compel short-term concessions, but they also encourage long-term adaptation. Canada’s Beijing pivot did not emerge overnight; it is the cumulative result of years in which reliability gave way to unpredictability in bilateral relations.

What happens next is uncertain. Washington could escalate, doubling down on tariffs and restrictions. Or it could adapt, accepting that influence now requires cooperation rather than coercion. Either choice carries costs.

What is already clear is that the pressure cycle has been broken. Canada has demonstrated that alternatives exist—and that once they do, the balance of power quietly shifts. In international economics, as in politics, leverage is most effective when it is rarely used. When it becomes routine, it teaches others how to live without it.