SAD NEW: Orca Trainer Devoured While Performing – A Tragic Wake-Up Call for Marine Parks

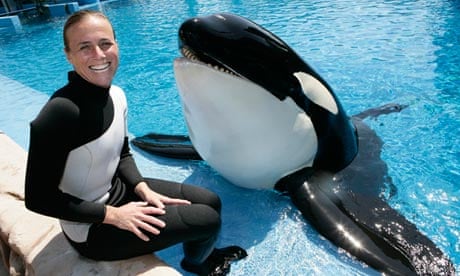

On a bright afternoon in April 2025, what was meant to be a thrilling performance at SeaWorld San Diego turned into a scene of horror. A 29-year-old orca trainer, known for her deep bond with a killer whale named Taku, was fatally attacked during a live show in front of hundreds of spectators. The incident, which unfolded just after 2 p.m., has reignited fierce debates about the ethics of keeping orcas in captivity and the inherent dangers faced by trainers. As the marine life community mourns, questions swirl about what went wrong and whether such tragedies can be prevented.

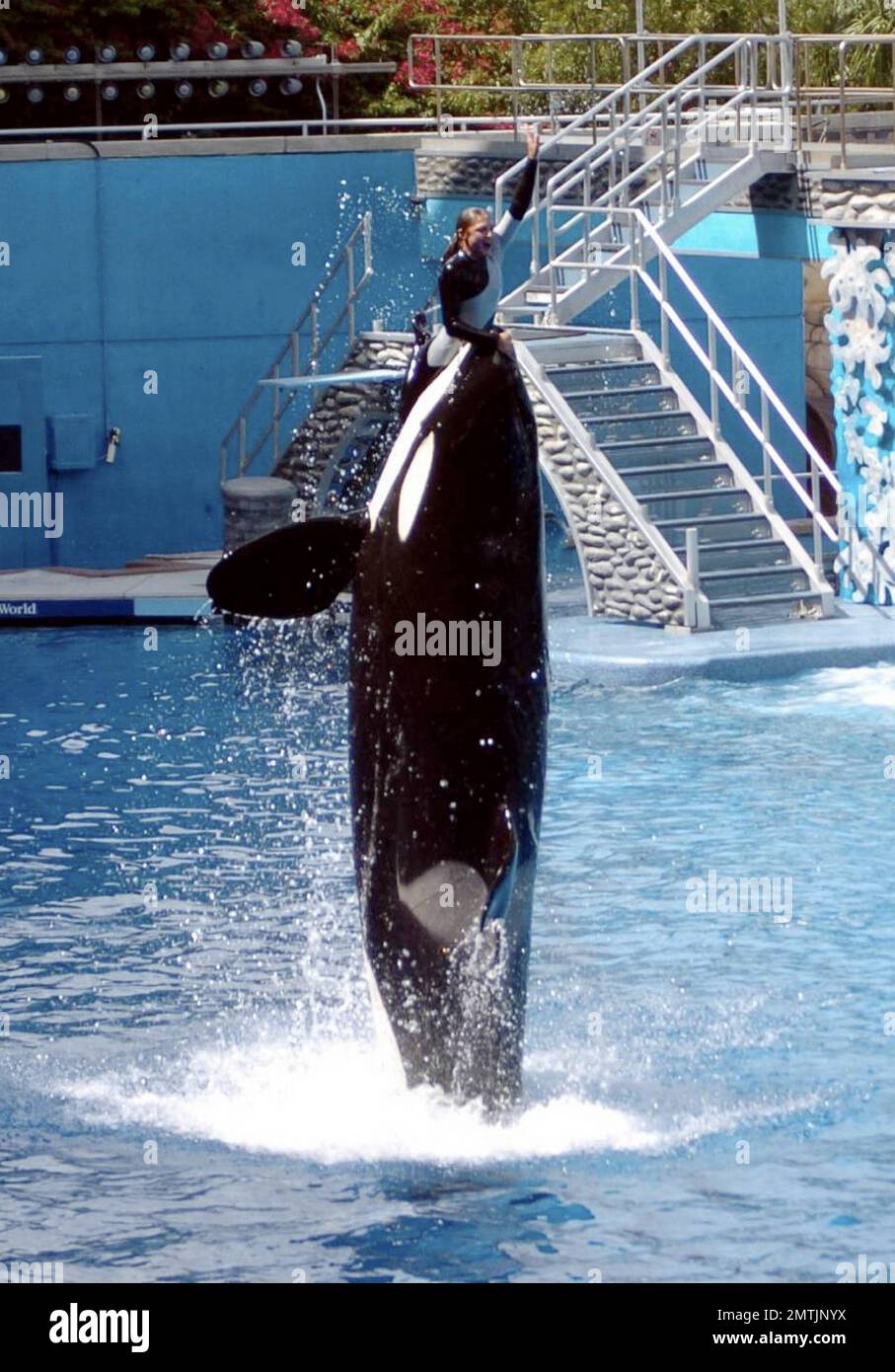

According to eyewitnesses, the show was proceeding as expected, with Taku, a 6,000-pound orca born in captivity, performing high-flying jumps and synchronized movements. “Everything seemed fine,” one front-row guest recalled. “Then, all of a sudden, the orca dove deep and came up under her so fast—it was like he wasn’t playing anymore.” Videos circulating on social media, many of which have gone viral, capture the moment Taku grabbed the trainer and dragged her underwater. Screams filled the air as staff rushed to intervene, but despite emergency efforts, the trainer could not be saved.

SeaWorld issued a statement expressing heartbreak: “She was an extraordinary human being who dedicated her life to the care and understanding of marine life. Our team is conducting a full investigation and will be reevaluating our safety protocols moving forward.” The trainer’s identity has not been officially released, pending family notification, but colleagues described her as passionate and experienced, with a particular affinity for Taku, who had been performing for over 15 years.

This is not the first time an orca has fatally attacked a trainer. In February 2010, Dawn Brancheau, a veteran trainer at SeaWorld Orlando, was killed by Tilikum, a 12,000-pound orca, during a “Dine with Shamu” show. Tilikum grabbed Brancheau, pulling her into the water, where she suffered drowning and severe blunt force trauma, including a severed spinal cord and torn-off scalp. Tilikum was also linked to two other deaths: a trainer at Sealand of the Pacific in 1991 and a trespasser at SeaWorld Orlando in 1999. These incidents, detailed in the 2013 documentary Blackfish, exposed the psychological toll of captivity on orcas and sparked a national conversation about marine parks.

Taku, like Tilikum, was born in captivity and has shown signs of unpredictable behavior in recent years, according to SeaWorld staff. Orcas, also known as killer whales, are apex predators with complex social structures and intelligence comparable to dolphins. In the wild, they roam up to 100 miles a day, living in tight-knit pods. In captivity, confined to small tanks and subjected to repetitive routines, orcas often exhibit stress-related behaviors, including aggression. The Blackfish documentary argued that such conditions make orcas more prone to lashing out, a claim echoed by animal rights groups like PETA following the 2025 incident.

Following Brancheau’s death in 2010, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) banned trainers from performing in the water with orcas during shows, citing drowning and struck-by hazards. SeaWorld was fined $75,000, later reduced to $12,000, and implemented safety measures like removable guardrails and high-pressure water hoses for interacting with orcas. Despite these changes, trainers still engage in close-contact activities during training and care sessions, as seen in a September 2024 incident at SeaWorld Orlando, where a trainer was injured due to inadequate protections, resulting in a $16,550 OSHA fine.

The 2025 attack has intensified criticism of SeaWorld’s safety protocols. Animal rights organizations, including PETA and The Whale Sanctuary Project, have renewed calls to end orca performances. “This was not a freak accident—it was a tragic consequence of keeping wild animals in tanks for human entertainment,” said PETA president Ingrid Newkirk. Social media has erupted with hashtags like #FreeTheOrcas and #EndCaptivity, reflecting public outrage. On X, users expressed grief and anger, with one stating, “Orcas don’t belong in cages. This tragedy was preventable.”

The debate over orca captivity hinges on their intelligence and emotional capacity. Orcas have complex language systems and strong social bonds, with some researchers suggesting their emotional centers are more developed than humans’. In the wild, no fatal orca attacks on humans have been recorded, yet in captivity, four deaths have occurred, three involving Tilikum. Experts argue that confinement in small tanks—equivalent to a bathtub for a human—causes psychological distress, leading to abnormal behaviors.

SeaWorld ended its orca breeding program in 2016, meaning the current orcas are the last in its care. The company has shifted to “Orca Encounter” programs, focusing on education about wild orca behaviors rather than theatrical shows. However, critics argue this change is insufficient, as orcas remain in captivity. “They can’t be released into the wild—they’d die,” one X user noted, highlighting the complexity of transitioning captive orcas to freedom.

SeaWorld has suspended all orca shows nationwide pending an OSHA investigation. Mourners have left flowers and notes outside the San Diego park, one reading, “She loved them, even when they turned on her.” The incident has reignited calls for sanctuaries where orcas can live in larger, more natural environments.

This tragedy underscores the fragile relationship between humans and captive orcas. While trainers like the victim dedicated their lives to these majestic creatures, the risks of working with stressed, powerful animals in unnatural conditions are undeniable. As investigations continue, the marine park industry faces a reckoning: can it justify keeping orcas in captivity, or is it time to rethink our approach to these intelligent beings? The loss of another trainer is a stark reminder that change is overdue.